A Good Man

by Elissa Matthews

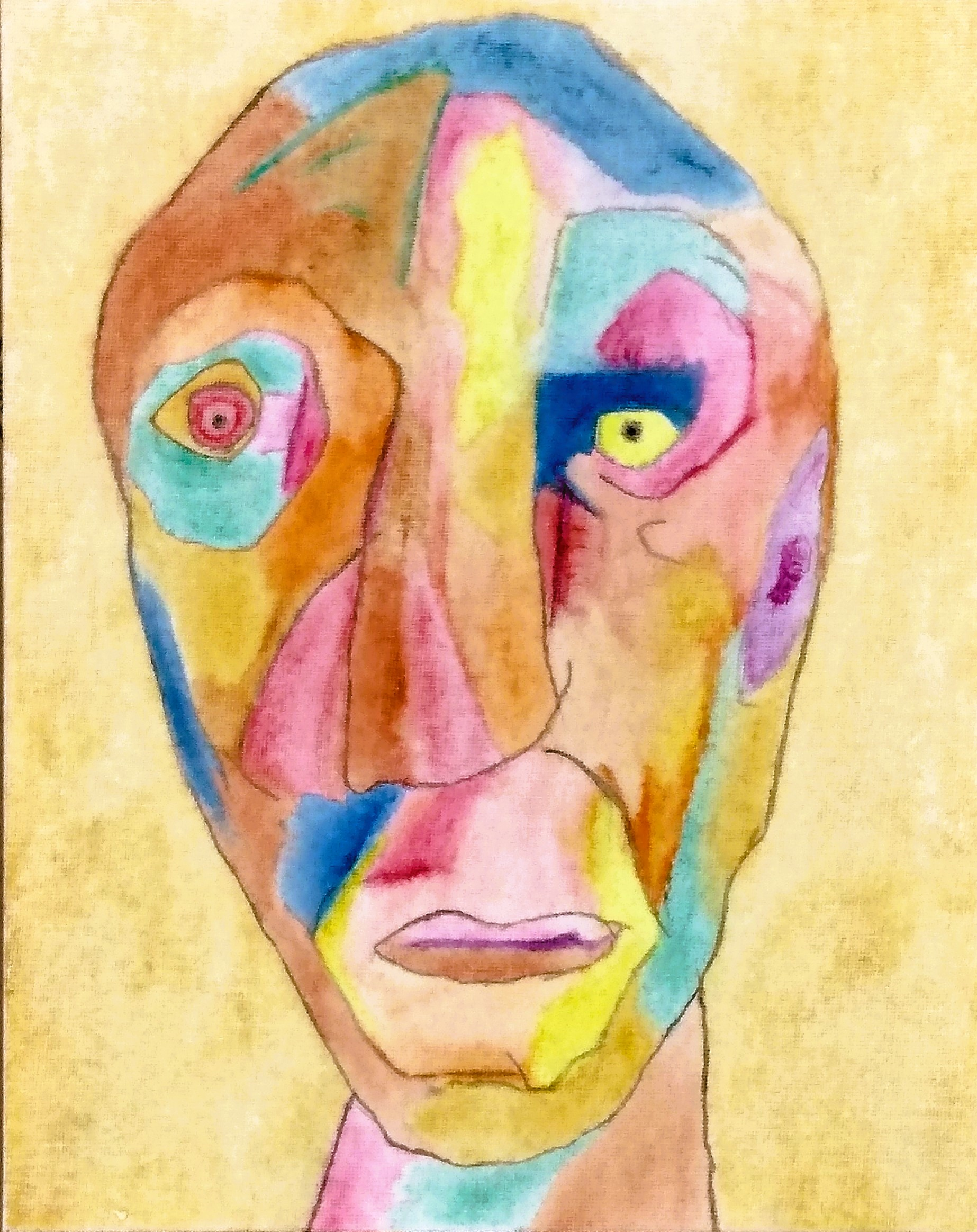

Art: “Edward” by Badfuta

He was a good man. Everybody said so. He taught woodworking and knot tying to the Boy Scouts, even after his own two boys were long gone to college. Good schools, both of them. He shoveled the snow from his walk without paying attention to stopping exactly at the property line, and shoveled the walk for Tessie Barks the winter she broke her arm in a fall on the ice. He religiously bought lemonade from any summer stand, no matter if the cups – or the child selling it – were slightly grubby. He didn’t fondle co-workers of either sex, and he never took credit for ideas or sales that weren’t his. He was inordinately patient about repeating things for his wife, who seemed to be a bit hard of hearing, or absentminded, or something. Nobody knew for sure. Everyone smiled when they saw him, and he smiled back, always stopping to talk if there was time and apologizing if there wasn’t.

He was just as good a man behind closed doors. He didn’t drink. He didn’t smoke or snort cocaine, he didn’t download pictures of teenage Serbian prostitutes. His children never had to wear long sleeves or calamine lotion and tell the teacher they had poison ivy. There was no one locked in his basement, or his attic – in which all the seasonal decorations were boxed and labeled - or behind a secret panel in the back of the toolshed at the end of his vegetable garden. He did more than his share of the chores, gently tucked a blanket around his wife if she fell asleep on the couch while he was talking about his day, and when he got angry he counted to ten, or walked away until he felt able to discuss the issue reasonably and rationally. He swam at the Y every day, and never even noticed if anyone else gained weight.

I first encountered him in the grocery store in town one afternoon shortly after my wife and I moved into town. He was ahead of me in line with his boys, who were probably 5 and 8 at the time.

“One candy bar to share,” he told them.

“I want that one,” the younger boy shouted.

“Inside voices,” he said.

“I hate peanuts,” the other shouted in a whisper. “I want caramel coconut.”

“Noooo!” the younger one wailed.

“We don’t have all day,” the cashier snapped. “There’s a line.”

“I’m so sorry,” he said, smiling at the cashier, then smiling at me. He picked up one of each candy bar, put them on the belt with the rest of the groceries, and then turned to the boys. “You will decide which one to share today, and which one will go in the cabinet for tomorrow.”

Just like that, the boys settled down and started negotiating.

The cashier rang up the goods while he bagged them.

“I certainly hope you’re paying cash,” the cashier announced when the bagging was complete. She stabbed a finger at the sign by her head. “This is a cash only line, you know.”

“I’m happy to pay cash.”

“I’d appreciate exact change as well.”

“I don’t have it, I’m so sorry.” He handed her the bills.

She glared at them, then put the money in the till. The register showed 78 cents return, but even from where I was standing I could see she had shorted him.

He looked at the money in his hand.

She slitted her eyes at him.

“That’s not the right change,” the eight-year-old said.

“Yes it is,” the cashier said.

“There’s a quarter coin not enough,” the little boy said. “We learned coins in school.”

“Then your father must have dropped it. I certainly didn’t.”

“But…”

The man put his hand on the boy’s shoulder and cut him off. When he put the money carefully in his pocket without a word, it didn’t feel like a gesture of weakness, of acquiescence to a bully, it felt like an act of generosity, of donating that quarter to someone who needed it more.

He smiled at the boys, at the cashier, at me, and walked away.

I bought my bread and roast beef and quickly overtook them just outside the exit where he was crouching down with his arms around the older boy, who was sniffling.

“But she was so mean to me.”

“I know.”

“I was right. I can do coins.”

“I know.”

“Why was she so mean to me?”

He paused for a minute, and I did too, pretending to be reading the flyers for pet sitters and house painters on the bulletin board. “Sometimes even grownups can be mean, a little bit. You never know what’s going on inside someone else’s head. Or maybe her feet hurt. Wouldn’t that make you a little crabby? It would make me crabby.”

Both boys nodded, and the little one wiped his nose on his sleeve.

I hoped I would be as good a father when it was my turn.

One crisp October morning after the kids had grown and moved away, his wife of twenty-eight years ditched her job and her cell phone, climbed aboard a gleaming black Harley with scarlet flames that matched the new ink on her bicep, and was last seen heading west on Highway 10.

Elissa Matthews was born, raised, and began work in New Jersey. At some point she got fed up, launched on a journey of discovery, and explored many distant corners of the world. One frigid day in November, at 6 in the morning, climbing into cold water scuba gear, she realized that maybe a 9 -5, climate-controlled job in an office somewhere (even New Jersey) wasn’t as bad as it sounded. She now has a husband, two sons, and a very stable desk job, in New Jersey. Her motto is: Let’s hear it for central heating!