Of Heaven and Hell and the Child Who Fell

by B.L. Meinecke

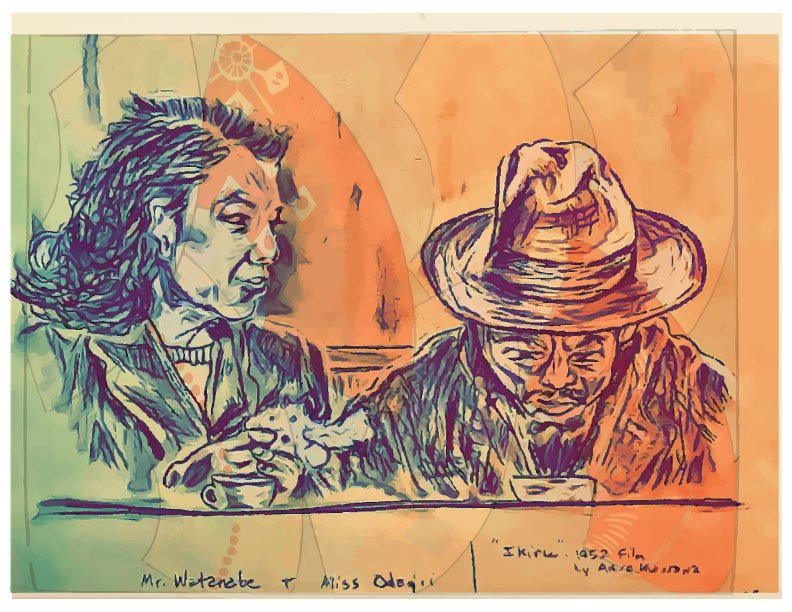

Art: Steve Simmerman - “Ikuri Duo”

Two 8-year-old boys — one named Mark, the son of a Japanese mom and an Italian WW2 veteran; the other, me, the son of an artist and an actress — stand in a gangway between two garages in Chicago’s Lincoln Park one fine spring day in 1963.

Concrete under gym shoes, dirt under and beside the concrete, butts up on the foundations of the twin garages; a thin tree looms tall over both. We stand there looking up at the roofs, our hands on the bark.

“We can really climb up there?” I asked.

“Yep,” said Mark, my close friend.

“Not only that,” he continues, “you can jump from there, to there, pointing over our heads to one roof then the other.”

“No shit,” I say.

In the spring of 1963, life is hunky-dory. Our belief in the many myths of society and America are strong and intact. We also foolishly believe that we have a complete working knowledge of all the realities life will insist we navigate. Ignorance is bliss, at least when you’re 8.

“Nicky showed me and Reed how to do it,” Mark said. “It’s easy, see? It’s fun, no one can catch us up there.”

We were in the same 3rd grade class at Lincoln School and lived a stone’s throw from each other, right down the alley behind 2022 north Cleveland in Chicago’s Lincoln Park.

Mark wasn’t an only child: his older brother Nicky, papa’s firstborn, is a large muscular kid two years older than Mark. Hell on wheels, aggressive, but a braggart. Not as bad-assed tough and experienced as his braggadocio would have you believe. Nevertheless, he was formidable. But since he was also pretty smart, he was frequently fun to be around, as long as you let him believe he was the alpha dog. Which was easy because, physically, he was.

Then there was Reed. The youngest, until the arrival of a younger brother in a couple years. Reed, unlike Nicky, was tough as nails. He could take it and dish it out. He was wild and crazy so fun to pal around with, but he had an unfortunate habit of injuring his head, having been sent to the emergency room 3 or 4 times in the last couple of years alone, always for stitches in his poor noggin.

“Are you sure man,” I say, “what if we fall through or somthin?”

“Then you’re fucked man cuz I aint fall’n through nut’n,” he says with a smile, pushing me.

Laughing, I push him back – hard!

Goofing around like this was common back then. It was the heyday of Chicago’s fake wrestling. The Bruiser and The Crusher were household names, and even those of us who understood it was fake watched them all the time, because they were hilarious.

I hated fistfights unless enraged because hitting hurts, giving and receiving. But wrestling was fun, at least most of the time. We’d have big tournaments in the grass with a mess of kids participating almost as often as we played baseball which was nearly every day.

Me, Mark and Reed were pretty evenly matched. Nicky was another story. Not one of us could take him individually; a fact we all hated! C'est la vie.

“Fuck!” I say, “Ok, man. I better not fall in any damn holes, but alright! Show me! You lead, I’ll follow.”

And up the tree he goes, then from the tree to the roof, me following. Easy as pie, I think.

Wow! Change position on this planet by a few feet and whammo, it’s a whole new world.

Ground far, sky near, or so it seems. Birds in the now much closer canopy of tree limbs chitter and bitch as I invade their space.

On my friends' exhortations, I leap through the air and soar, my feet finding purchase on the hot tar of the garage roof on the other side of the gangway.

My brain overloads with pleasure. I AM FREE! Completely unsafe. Perfectly unattended, other than by the whims of the universe. And I can fly! Or at least that’s how it feels. Based on the feedback from the birds, I’d say that feeling just might be a reality. I’m in heaven!

All I’ve done is climb onto a roof, then leap to another. Who knew freedom was so close and so easy to obtain?

My friends knew, that’s who: Nicky, Reed, Mark, Henry, Alan, KJ, Wendall, Dave, Fred, Hans, Robin, Dickie, Tommy, Emilio, Danny C., and many others, all lived within a couple of hundred yards of each other.

Economically, most were middle-class, some were lower: Japanese, Cuban, Puerto Rican and white — a pack of all-American kids on the loose.

They’re the ones whose exhortations shamed me into taking that first leap into space, soaring through the air, landing on someone’s garage roof on the other side of the chasm over which I’d just leapt. I love this world they’ve shown me. The best part? Adults can’t come here! Not even cops can catch us up here, I think to myself naively.

Shit, I thought, I may move in, picturing myself shooting squirrels and birds with my sling shot for food, drinking from back yard hoses and eating stolen garden veggies. Arrrr, a pirate's life for me! Like the Disney song. Or better yet, like Robin Hood in the Sherwood Forest. Or Peter and his Lost Boys. Or the Swiss Family Robinson, but on the roofs of Chicago’s garages.

Young male fantasies are powerful sometimes. We all had them. They tied us together in a way; were something we shared. For a few years there we were pretty inseparable — me, Mark, Reed and Nicky. Though Nicky somewhat less so because he had “big kid” stuff to attend to.

They were a pleasant alternative to the poor Appalachian white kids who lived in the cavernous, 6-story high, President Hotel on the tri-corner of Cleveland, Dickens, and Lincoln, about half a block north of my house.

These kids seemed to be perpetually enraged, and they hated me at first sight. Apparently because I had things, read books, had parents who didn’t beat me or each other or start fights with our relatives, and also, according to them, I lived on the wrong side of the street. I kid you not.

So my peers and I roamed the neighborhood, protecting each other from the big kids and the hillbillies, stealing Playboys from the corner store, catching grasshoppers and crawdads to scare the girls, collecting knives, collecting empty pop bottles for easy money, playing baseball, playing army on our blocks and at the park, stealing cigs from cars, throwing firecrackers, establishing secret clubhouses, riding our bikes everywhere in huge possies, shooting things and each other with slingshots. And now, jumping roofs. Life was good!

In 1963, Lincoln Park’s alleys all had garages separated by gangways. The alley separating Mohawk and Cleveland between Armitage and Dickens, after the first few northern-most properties, could be traversed almost end to end entirely in the air — if one was brave and if one avoided the hazards.

One roof in particular was dilapidated, kids fell through it twice that I know of, which at the time no one thought was a big deal somehow. The kids healed, no one sued; we kept playing, the roof unrepaired.

The other hazard was two garages separated by a double gangway and a big old tree. You had to jump from one garage roof to the tree, then perched on the fork of one of its big old branches you’d leap onto the next garage.

We navigated this hazard easily until one day, some poor kid didn’t.

I didn’t know his name, but I knew him as part of a pack of slightly older kids I’d commonly encounter playing on the streets and alleys of Lincoln Park. He was fat-ish for the day, pudgy and soft. But with a hard face that bespoke of hard parents and a hard life. He was poor, based on his clothes, and wore eyeglasses — at the time, an expensive proposition for some. Don’t think his folks had much money, so pretty sure they resented the glasses.

People get crushed by life sometimes. By forces bigger, greater than themselves, than us, than anyone. Sometimes when this occurs, we become devoid of normal human emotion. It happens! Sucks when it happens to you, or worse to someone who watches over you . . .

That day, I was in a group of about 10 or 15 kids of varying ages playing roof tag, a dangerous “sport” that involved tagging people in midair sometimes, though that wasn’t what happened to the kid.

We were playing as normal, advancing north to south, flying from roof to roof. As he reached the garages separated by the tree, he got on just fine. But when he pushed off to jump to the next roof, his foot slipped in the tree fork. He dropped like a stone, shattering his hip.

I’ll never forget the sound his body made when it hit the concrete.

He lay there in the gangway — broken, crying, screaming!!! I’ve never seen anyone so hurt or so sad. His sobs were from pain, but the fear and hopelessness I saw plainly on his face were not. He knew how his parents would react. He knew his life was effectively over. He wailed, shrieking in pain and misery, firmly ensconced in hell on earth.

Grownups gather as the child shrieks on the ground. Shouted accusations and recriminations stupidly began to fly among them. It was obvious there wasn’t much they could do for the kid, so they turned on each other like a pack of monkeys. My disdain for grownups, in fact for all authority figures, exponentially multiplies as I watch this display.

The ambulance coming to cart him away scatters the bickering adults. Its attendants hop out, take one look, and jab him with morphine. Or at least I assume it was morphine: medical pain relief was fraught at the time. Then, using a canvas sling type of deal, they get him into the ambulance clucking over his sad fate as they cut away his clothing — his shrieks having quieted now, though he still shivers and moans.

Some of us stayed on the roofs during the whole event, moving back and forth between them, soaring over the sobbing boy, perching sometimes on the spot from which he fell.

We never saw him face to face again; except, every once in a while, we’d see him standing, holding the railing of his wooden third floor porch, looking down at us or staring blankly off into the distance. We’d wave or shout; he’d turn away.

Every! Time!

We didn’t blame him but finally we didn’t bother. Then he’d stand there for hours, watching us and the world, never saying a word, until he moved away a few years later.

His parents couldn’t afford the total hip reconstruction needed, so, instead of giving it to them, to their child, which we, society, could’ve easily afforded to do, the docs did a cheap fix, a fix that left him permanently crippled with little use of one leg. So there we have it — a life broken by a misstep and an absence of compassion. It was hell on earth for him after that.

Siren wailing, the ambulance pulls away. Those of us who’d found the ground to try to help or watch-over returned to the pack, the steam sucked out of us by the accident.

Deflated, ignoring any lingering adults, we gather on a sturdy flat-roofed two car garage a few lots down where no authority could reach us or even discern our presence.

There we sit, huddled together, somber, sobered by the event, a few older kids pass around cigs and lights, sunshine through the branches paints us with light and shadow . . . Sitting there close on the roof’s warm tar, sheltered by each other and the trees filled with birdsong, we smoked and talked slowly of:

life and death,

the blue sky above,

God and the devil,

heaven and hell,

and the fate of the poor child who fell.

Author’s note: We, the children of Lincoln Park, never stopped roof jumping. For all I know “we” do it still, in fact, I’d bet on it!

Enjoy this momentous day!

Born in Chicago in 1955, B.L. Meinecke has been involved in street gangs, professional bands, raising a family, and successfully running small businesses. His knowledge is eclectic, as are his stories.