The Class Rebellion and Subterfuge

by John Haymaker

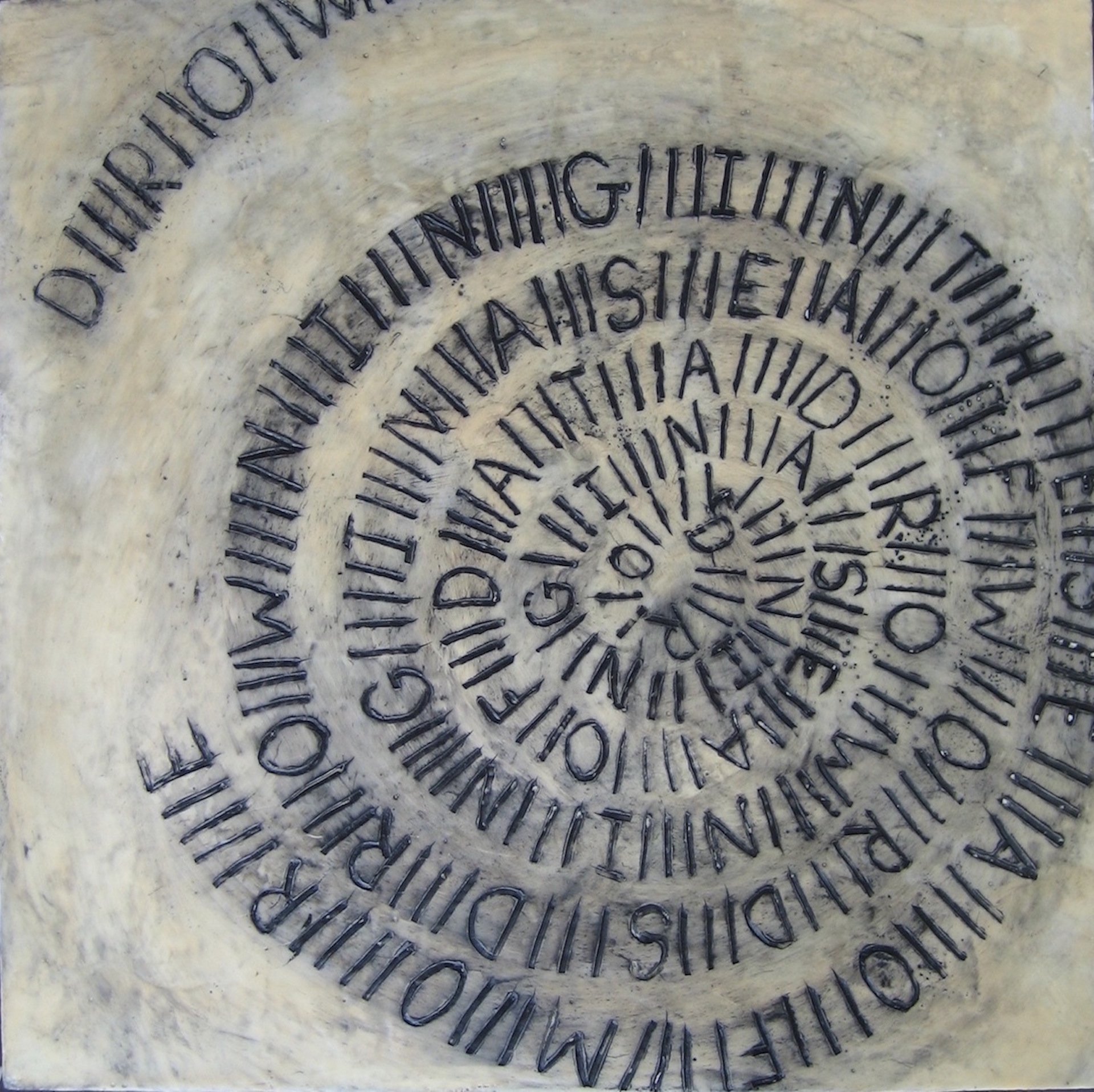

Art: “TEXT NOISE” by Michael Teters

1967. Grade four. Howie repeatedly checked out a volume entitled, You Can Write Chinese. It was a thin, illustrated children’s book wider than it was tall, teaching rudimentary Chinese through stylized calligraphy. His interest inspired my curiosity and I took the book home myself a few times, unaware of the impact it would have on me. Many of the characters were pictographs, those few hundred derived from ancient drawings and still vaguely depicting objects, such as 日 rì (sun – as if on the horizon), 木 mù (wood – like tree branches and roots), and 東 dōng (east – the sun rising through branches). Fairly simple stuff kids could grasp.

Beyond Howie’s fascination with the book, I never knew a lot about him. He had overly large ears and smiled a lot, revealing equally large dimples. He stood taller than me, but appeared meek with a slight stoop in your posture. He kept to himself, withdrawn and never wanted to talk. Yet Howie had more influence on my life than our gray haired schoolmarm, Miss Knepper, whose leather tough cheeks seemed always flush with anger.

When she called on him, Howie’s dimples and smile flashed briefly, but unable or unwilling to respond, he shrugged and hung his head. Reading and vocabulary especially lessons never went well for him. One week he spelled God backwards, and Miss Knepper berated him – as if he’d made a slur of His name on purpose.

If she was clueless that Howie somehow saw the letters differently, it was obvious to me there there some disconnect going on, but I didn’t have a word for it yet. I know now that he had dyslexia. He was differently-abled and Miss Knepper was unprepared to help him learn – yet Howie decided to teach himself some Chinese.

I wonder if his attraction to the language might have been related to his dyslexia: I’ve read that different writing systems present dyslexics with different challenges – other than reversing first and last letters. Symptoms for Chinese dyslexics may include confusing similar looking characters when reading or struggling with proper stroke sequence when writing – neither of which seemed to diminish Howie’s preoccupation. Chinese perhaps freed him from his struggles with the alphabet and allowed him to engage comfortably with written language, perhaps providing shape to the abstract English letters.

He seemed to find refuge in that book. Once or twice I saw him reading it in his lap during class while ignoring Miss Knepper’s lesson. I recall how Howie’s eyes and face lit up brilliantly at times and he’d grin staring at the page.

He was definitely in his happy place until a few weeks later. After library period when Miss Knepper routinely visited each student’s desk to review our book selections, she found Howie had chosen that book yet again. She snatched the book away from him with one hand and waved a finger in his face with the other, forbidding him ever to check it out again.

A week earlier Miss Knepper had choked me for choosing A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. Innocently enough, the cover art juxtaposing an inner city neighborhood with an amazing bridge in the distance captured by imagination as I thumbed for a new selection that week. As soon as Miss Knepper stopped by my desk, however, her forearm wrapped tightly around my neck. Picking up the book with her free hand, she flipped it open, sternly informing me she hadn’t read it until college. She released her chokehold only upon realizing my selection was an abridged version for adolescents – her bad.

The following week, as I watched Howie half-heartedly browse library books, I came to his aid. I checked out You can Write Chinese myself. His sudden smile said it all as I passed it to him discretely after library period: the book was a lifeline. Thus began a year-long campaign by others in the class to do the same. Prior to the next library period, he returned the book without fail to whichever of us had loaned it to him.

Miss Knepper was surely wise to our subterfuge since one of us always had it checked out. Perhaps she didn’t dare let on or punish us because of the note my mother had written to the school, explaining that I was allowed to read any book I chose. My mother wrote her a note informing her that I was allowed to read any book I chose.

I had forgotten that incident until I enrolled in college and found Mandarin was an option to satisfy the foreign language requirement. Howie’s passion and our subterfuge sprang immediately to mind. I enrolled, even if Mandarin was a daring enterprise for me – I’d never been especially talented with French or Spanish in senior high. As you would guess, I was soon mesmerized by the musicality of Mandarin and the system of writing. What a wonderful choice I made. Howie’s fascination became mine.

After graduating, I jumped at an opportunity to teach ESL in China. My Chinese students asked how I got interested in Chinese and were delighted to hear the tale of Howie and me – proud their language had inspired another sort of “class” rebellion.

Today, as books are pulled from library shelves and out of kids’ hands, as libraries are defunded and even closed, Howie’s and my subterfuge seems especially relevant. Something akin to a collective dyslexia has taken root in Miss Knepper-ish school boards, transforming LGBTQ guidance materials into grooming, transposing literature into smut and even transfiguring Michelangelo’s Figure of David into pornography.

Howie’s and my fourth grade class responded with defiance in the face of a very ugly attempt to intimidate our reading. But then as now, prohibition serves to create more curiosity. Fortunately, nothing is out of reach on today’s internet. I still read Chinese daily partly inspired by events in fourth grade – and I remain attuned to the kind of honesty I found in A Tree Grows in Brooklyn.

John Haymaker's recent LGBTQIA+ stories and nonfiction appear in various online journals, including The Bookends Review, Hawaii Pacific Review, Cosmic Double and Across the Margin. Chinese to English translations appear online at Bewildering Stories. After giving away nearly all his material possessions except the ridiculously heavy piano keyboard and

iMac, John writes as an American expat in Portugal, where he lives with his partner of 28 years. Find John online at https://johnhaymaker.com