The Imperative of Protest

by Ben Roth

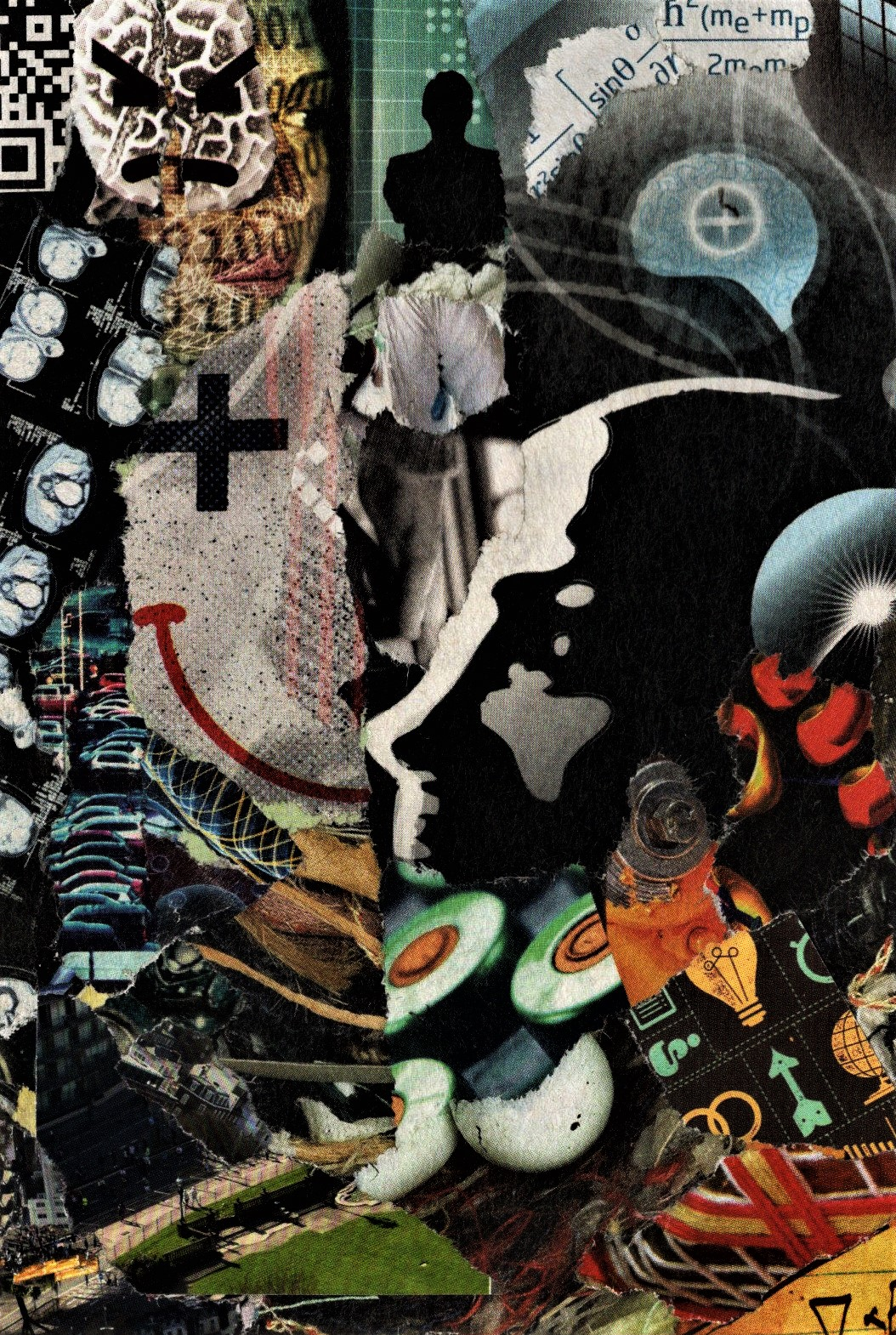

Art: “When the Clown Equation Doesn’t Add-Up”

by Janina Karpinska

Dress simply: jeans, pullover, running shoes.

Don't forget your backpack. You won't need many things, but these you will: your two water bottles, carefully filled ahead of time, shaving cream, a sandwich, cigarettes, Metrocard, your lucky lighter, Guy Fawkes mask.

Leave your wallet and keys on the desk. It will be better not to have them on you. If necessary, your roommates can let you back in. But it won't be necessary.

Don't take a last look around. Just pull the door shut behind you—quietly so as not to wake anyone. Remain focused on the next step. And the next.

Take the subway downtown. You have never been able to afford a place closer in, and have had to work two jobs to (barely) afford this one, so have always had a long train ride. Savor the irony that, this time, you will not be bored. This time, you wouldn't mind if the trip took even longer.

Notice the other passengers this time of night, or is it morning? Immigrants, with thermoses of coffee and tea and carefully packed breakfasts and lunches, coming from even farther out in the borough, on their way to work when most people—including yourself, usually—are still asleep. As you get closer in, students, half passed out from too much drinking, on their way back to ideally-located, parentally-subsidized dorm rooms. Yet farther in, a handful of bankers, carefully protected by their suits, ties, headphones, and newspapers. Often their ties are pink. Sometimes their newspapers are as well. Once you saw a guy with a pink newspaper, pink tie, and pink shirt. He caught you staring. You merely blinked, but he blushed, his face becoming pink as well: he knew it was too much. You should not resent these bankers. They are only up this early because they have yet to make the varsity team. They must have everything ready for their superiors by the time the sun rises, or are only going into the city to catch a train yet further out to New Rochelle or Stamford, where their lesser banks can afford office space. And they are riding the subway, not taking taxis, much less private cars. You should not resent these bankers, but you do.

Don't miss your stop. Get off the train. Throw away your now empty Metrocard. Exit the subway.

You know this neighborhood. There is City Hall, where they have ignored you. You have tried the Times too, and they have ignored you as well.

Find a quiet spot to sit. All the spots are quiet right now. There are taxis and town cars on the street, as there always are, but they don't need to honk at this hour. All professionals, they move in an orderly manner, letting each other merge, cross three lanes, pull U-turns with a courtesy they would never grant amateurs.

Remember the plan. The plan is to go just before sunrise. The plan is to get video on the morning shows. The plan is for most of the city, those still asleep now, to wake to the news.

Take out your sandwich. Ignore the fact that you have no appetite. It will settle your stomach. You will need the energy.

Don't think about what they have taken….

Look at the trees. There are not enough trees downtown. The ones that remain, even those that have been added, even those marooned on small islands of dirt amidst the sea of concrete: they should be appreciated. You have spent long hours in parks on mild autumn days watching trees move in the breeze against the perfectly blue sky. You have spent long hours walking the city at night, unable to sleep for worry about unpaid bills, unhappy relationships, unrealized ambitions. At night, it is the buildings you notice. The line of red lights stretching into the distance on one avenue, white lights on the next. The airplanes moving overhead, the boats on the river. You have not spent long hours watching trees at night. Spend a few minutes now.

Get into position. There is a spot here between two planters that no cameras cover, as far as you can tell. It is just outside the plaza. People think it is a park, with its benches and sculptures and water features, but it is not. You can eat your lunch there, you can sit and drink a coffee, you can talk to a friend for a few minutes, but only if they don't object, only if the corporation doesn't think you might possibly harm their image or shiny new headquarters. In fact, the city does own the land, but they don't think it is worth paying to care for; because the corporation does, they get to say what goes. Linger too long, stretch out in the sun thinking you might take a short nap, and you will be asked to leave. Sit down with too many bags—not shopping bags emblazoned with the right brands, but an old frame-pack, and suitcase, and trash bags filled with your worldly possessions, and you will be asked to leave. Retrieve people's discarded cans and bottles from the trash cans, or dare to light a cigarette—you won't believe how fast the guards come running. Bother too many people with questions, get a reputation, and you will be asked to leave. The corporation doesn't like the way these things look, and the city is on their side, not yours.

Don't think about how this place should not be theirs, is not theirs. Don’t think about those who did care about this place and what happened….

Give up trying to think of the corporation, of the city, as persons. People are anonymous; corporations are visible. Therefore corporations are persons, and people are not.

Make them see.

Take the shaving cream and mask out of your backpack. You know that the guard detail switches after sunrise. There are many during the day, but only one overnight. He mans a bank of CCTV monitors and makes occasional rounds on foot—but never near the end of his shift. You suspect that he falls asleep by the end of most nights or at least doesn’t pay close attention to the monitors. But the monitors monitor even when no one looks at them. The video can be replayed.

Your mouth is dry. You wish you had something to drink.

Are you ready? You are. Pull the mask over your head. Grip the shaving cream, despite your sweating hands. Go.

The first camera is on that lamppost, but if you stand on the back of the bench beneath it, you can reach. Spray shaving cream over the lens.

Move quickly to the other corner of the plaza. This camera is on the wall. Take it in both hands and carefully redirect its line of sight.

Circle the building now, obscuring the cameras pointed at the surrounding sidewalk. You cannot direct the world’s attention away from screens, but you can redirect it to the right ones.

Back is the plaza, climb the gate. The plaza connects to an inner courtyard. During the day, it seems to be part of the plaza, which seems to be a park, but the courtyard is really owned by the corporation, and is even more heavily policed. At night the connecting underpass is gated, but it’s an easy enough climb.

You expect you have the guard's attention now—the camera you re-angled is pointed right at the gate. Hurry.

There are four cameras in the courtyard. Re-angle the first, above the door, to point at the right spot. Ignore the shout of the guard from inside the building.

Climb the ostentatious stonework on the other side of the courtyard and re-angle the second camera. The third and fourth are already pointed the right way.

You can see the guard now, fumbling with his oversize keychain, trying to unlock the door. Try not to feel pity for him.

Open your backpack. Take out the first water bottle. Pour it over your head.

Resist the smell.

Take out the second water bottle. Pour it over your head.

Notice the unfamiliar viscosity. Resist the urge to gag.

What is this voice inside you that tells you what cannot be endured and so what must be done? Do other people not have it, or do they just not listen?

Take off your mask. Assume the precise position you have imagined.

Look, one by one, into each of the cameras now pointed at you.

Look at the guard, who has now made it out the door, but, sensing that something is wrong, has hesitated from coming any farther. Make eye contact with him. Blink once, decisively, as if to say: I am aware of what I am doing. I am in my right mind. I choose this.

Take out your lucky lighter. Strike it.

Once you've gotten this far, let the rest take care of itself.

Burn.

Die.

Protest.

Ben Roth teaches philosophy and writing at Tufts and Harvard. His fiction has been published by Nanoism, Flash, Blink-Ink, Sci Phi Journal, Aesthetics for Birds, Cuento Magazine, 101 Words, decomp journal, Bodega Magazine, Gambling the Aisle, Sensitive Skin, Euphony, and Your Impossible Voice, and his criticism by Chicago Review, AGNI Online, 3:AM Magazine, The Millions, and The Chronicle of Higher Education.